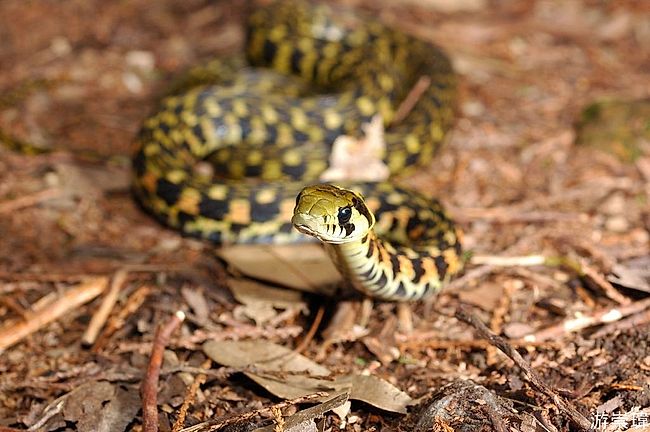

Rhabdophis tigrinus formosanus

Asian Tiger Snake

台 灣赤煉蛇 (tai2wan1chi4lian4she2)

Status: Protected (Cat.II)

VENOMOUS!

Family

Colubridae, subfamily Natricinae

Max. length

100 cm

Occurrence in Taiwan

Throughout Taiwan, at altitudes above 1500 m. Rare.

Global Distribution

This subspecies is endemic to Taiwan.

Description

Small to medium-sized snake; total length up to 100 cm. There are 15-19 (17-19 at mid-body) rows of scales, all are strongly keeled. Head is oval and distinct from neck; body is moderately stout; tail is moderately long. Eye is medium to large; iris is dark brown and pupil is round, jet black, surrounded by ring of gray. Tongue is maroonish. The snake has a pair of nuchal glands and enlarged rear fangs (not directly connecting to venom glands). Upper head is olive at least anteriorly; there is a thick, curved cross band of yellow on the nape, to which a black cross band adjoins in the front and rear. The supralabials are yellow with black sutures, the black areas along the sutures below eye are broad. Upper body and tail bear green/yellow/orange and black spots arranged in alternating rows (totally 5 rows), creating a checkered appearance. Ventral head is whitish. Ventral scales on body and tail are blackish with (irregular) posterior margins of light green/yellow. Anal scale is divided and subcaudals are paired.

Biology & Ecology

This diurnal opistoglyphous (= rear-fanged, see footnote (1)) snake inhabits humid environments, including mountain rivers, creeks, and forest floors. It preys on frogs and toads, and occasionally on fish or snakes. Females produce 8-47 eggs per clutch in summer; hatchlings measure about 16 cm in total length. When threatened, the snake may rear its head and neck, and expand its neck transversely like a cobra.

This species is also the only known snake that is venomous and poisonous at the same time. (For the difference between the terms 'venomous' and 'poisonous' see footnote (2)).

Here's how:

POISON:

The defensive behavior of this snake is very unusual. When threatened by a predator, the snake arches its neck toward the attacker and releases the contents of paired nuchal glands that lie in the dorsal skin. The product of those glands is distasteful and irritating to the eyes and contains compounds similar to those found in the skin glands of toads. (Source)

The origin of the poison in these glands is a highly interesting aspect of this species, and was explained for the first time in a 2007 study by Hutchinson et al. The study shows that Rhabdophis tigrinus becomes poisonous by sequestering toxins from its prey, which consists of venomous toads. The process allows the snakes to store in their neck glands some of the toxins from the toads they have eaten:

Analyzing differences between snakes living on toad-rich and toad-deficient islands in Japan, researchers led by Deborah A. Hutchinson of Old Dominion University in Norfold, Virginia, found that the Japanese grass snake or Yamakagashi, as the snake is known locally, did not manufacture its own venom, but instead relied on that found in toxic toads: the researchers found that snakes living on Japan’s toad-free island of Kinkazan lacked the toad’s toxic bufadienolide compounds completely. Snakes from Ishima, where toads are plentiful, had high levels of bufadienolides. R. tigrinus from Honshu, where toad numbers vary, displayed a wide range of bufadienolide concentrations. Feeding R. tigrinus hatchlings toad-rich and toad-free diets confirmed these results.

The study also found that snake mothers with high concentrations of the toxin are able to pass bufadienolide toxin on their offspring, helping protect them from predators. The Yamakagashi stores the sequestered toxins in 'a series of paired structures known as nuchal glands in the dorsal skin of the neck,' according to the researchers. When threatened, the snake takes a defensive position that exposes the toxin-containing nuchal glands to predators.

While sequestering defensive toxins from prey is unusual among terrestrial vertebrates, it is not unknown. Research published last year by Valerie C. Clark of Cornell University showed that poison dart frogs (Dendrobates species) and their Madagascar counterparts, the Mantella frogs, sequester toxic skin chemicals, called alkaloids, from the ants they eat. These alkaloids protect the frogs from predation. Similarly, some garter snakes are known to store tetrodotoxin from ingested newts while birds in New Guinea appear to sequester poisons from insects. (Source)

The NewScientist notes:

What is more, when attacked, snakes on different islands react differently. On Ishima, snakes stand their ground and rely on the toxins in their nuchal glands to repel the predator. On Kinkazan, the snakes flee. 'Snakes on Kinkazan have evolved to use their nuchal glands in defence less often than other populations of snakes, presumably due to their lack of defensive compounds,' says Hutchinson. Moreover, baby snakes benefit too. The team showed that snake mothers with high toxin levels pass on the compounds to their offspring. Snake hatchlings thus also enjoy the toad-derived protection.

VENOM:

Many members of the family Colubridae that are considered venomous are essentially harmless to humans, because they either have small venom glands, relatively weak venom, or an inefficient system for venom delivery. While Rhabdophis tigrinus has small venom glands and delivers its venom inefficiently, said venom is certainly not weak. Although this snake is reluctant to bite, even defensively, the bite has been known to cause fatalities in humans. The venom acts very slowly, inhibiting the ability of the blood to clot and causing death by hemorrhage:

"Three cases of serious envenomation by this species are reported (in Japan), all marked by delayed, spontaneous, superficial hemorrhaging and profound impairment of normal blood coagulation. In two cases these phenomena were accompanied by signs of severe internal hemorrhaging and hemolysis. Other symptoms may have resulted from transitory involvement of the central and autonomic nervous systems. Therapeutic measures applied in these cases are described, including the apparently effective use of a systemic antihemorrhagic drug. It is concluded that R. tigrinus is a dangerously venomous snake and potentially lethal to man." (Source)

For this reason, the small colubrid snakes of the genus Rhabdophis have a shady past in the pet trade. Because they resemble certain harmless garter snake-like species, they were imported into the U.S. and U.K. under the wrong names, and ended up causing medically-significant emergencies when they bit their new owners. (Source)

Etymology

Rhabdophis comes from the Greek words rhabdos, meaning "rod" or "wand", and ophis, meaning "snake";

tigrinus is Latin for "tigerlike";

formosanus denotes the distribution of this subspecies, namely the island of Taiwan (formerly Formosa).

The Chinese name 台灣赤煉蛇 means "Taiwan (台灣) Red (赤) Smelted (煉) Snake (蛇)".

Footnotes

(1) "Opisthoglyphous snakes are similar to aglyphous (fangless) snakes, but possess weak venom, which is injected by means of a pair of enlarged teeth at the back of the maxillae (upper jaw). These "fangs" typically point backwards rather than straight down, possess a groove which channels venom into the prey, and are located roughly halfway back in the mouth, which has led to the vernacular name of "rear-fanged snakes". (Source)

(2) The distinction between venom and poison

There is a difference between organisms that are venomous and those that are poisonous, two commonly confused terms applied to plant and animal life:

- Venomous...refers to animals that deliver (often, inject) venom into their prey when hunting or as a defense mechanism.

- Poisonous, on the other hand, describes plants or animals that are harmful when consumed or touched. A poison tends to be distributed over a large part of the body of the organism producing it, while venom is typically produced in organs specialized for the purpose. (Source)

Further Info